– Welcome to NOAA Live Alaska. My name is Lisa Hiruki-Raring and I'm going to be

moderating today's webinar. This series is a collaborative effort by NOAA Fisheries, Alaska Fisheries Science

Center, where I work. NOAA's Alaska Regional

Collaboration Network and NOAA's National Weather Service. This webinar series is

designed to help you get to know NOAA's work in Alaska and how we connect and

work with your communities. NOAA, the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration studies the ocean and the atmosphere and where the two meet

from weather to ocean, to the animals that live around us.

All of our speakers work

for some part of NOAA or work in partnership with NOAA. We hope this gives you a sneak peek at different career paths

you might be interested in. Today, we're introducing

you to Crane Johnson who works for NOAA's

National Weather Services, Alaska Pacific River Forecast Center in Anchorage, Alaska. Well, we'll be talking about NOAA's role in research and stewardship. We want to recognize that

we're all coming to you from the traditional lands

of native communities who have substantial indigenous knowledge and much to share with us. In Alaska, Crane's work is

conducted all over the state, which include the traditional homelands and waters of the Siberian Yupiit, Athabaskans, Unangax, Alutiiq, Sugpiaq, Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian. We are honored to acknowledge that Crane is presenting webinars

from Anchorage, Alaska at the ancestor land

of the Dena'ina people who are stewarded this area for thousands of years. The community thrives thanks to their continued sharing of vision, wisdom, values and leadership. We'd also like to acknowledge that we're hosting this webinar from the traditional lands of

the first people of Seattle, the Duwamish people, past and present.

A few guidelines before I

hand you over to our speaker. You're all muted because we have a lot

of people on the line and we want to make sure

everyone can hear our speaker. However, there's a box where

you can write questions and we encourage you to ask them as we go. My colleague, Chris Baier and I will be keeping track of questions for Crane behind the scenes.

We'll stop every now and again and answer a few questions. We might not get to all of our questions, but we'll try to answer as many as we can. All right, I'll hand it over to Crane to introduce himself. – Thanks, Lisa. Can you hear me and see me okay? – Yep, looks good. – Great. Hey, thanks everybody for joining us. And thanks Lisa for

that great introduction and inviting the RFC to

present in this webinar series. I'm excited to do that and

share what we do up here in Alaska for Alaskans. A quick look of what

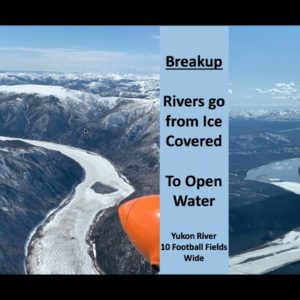

we'll talk about today. We'll start off with just hydrology and the National Weather Service. Provide a little bit of a background, my background, how I got into hydrology. Why I think it's so interesting. We'll go in and look at

a breakup and ice jams. We're right in now in Alaska, we're sort of at the front edge of our breakup period. And it's a time when you see in this picture to the right, most of our rivers are ice covered.

And so, it's the time when we expect that that ice covered a breakup and our rivers to open up. During breakup, we have a

program called River Watch. It's sort of our eyes in

the sky to monitor breakup. We'll look at that. And then towards the end, I'll provide a little bit of an outlook for what we expect with

this year's breakup. Before I go to the next slide, we'll just look quickly

at what is a hydrologist. And so, hydro comes from

the Greek word for water and hydrology is the study of water. So, hydrologists are

scientists who study water. A little sort of how I

got started in hydrology. I grew up on the East Coast of the United States, Pennsylvania. I moved to Alaska in 1995 and went to the University

of Alaska Fairbanks and got a degree in civil engineering. Then I had a few different jobs. I was always very interested in water and then came back to work

for the federal government both for the Corps of Engineers and then for the National Weather Service as a hydrologist.

If you're interested in hydrology, curious about careers in hydrology, especially in the weather service, there's a great website

that they've put together. You can sort of read my story and a few other folks story

from across the country. It sort of gives you an idea

of how we all get into it. I think one thing is in common, all hydrologists really enjoy water. I've always been interested

in water as a young kid all the way through college. And in my career I'm still

fascinated by water and ice. Quickly to get there as

you can just Google search NWS careers in hydrology. So, this is how I look at Alaska, the map in the top. It gives you some perspective

of where Alaska is compared to the lower 48, the US lower 48 states. We're off to the West

and we up to the North. But when I look at Alaska,

I think about Alaska, I tend to focus on rivers. I think most people

look at maps with roads. And so, I always enjoy this map that just it's our state

with our rivers shown. Always one of the rivers

we're most concerned with and this year is no exception, is the Yukon River there, shown in red.

And the Yukon River is

the third longest river in North America. And if you sort of stretch the Yukon River from end to end, it'll go from the West Coast of California all the way East to about Alabama. The other thing that's really important with our rivers in Alaska is, that's where communities are, that's where people live. And so, you see that just

about every community outside of Anchorage and Fairbanks are located on one of our

rivers around the state.

I think as a hydrologist, one thing I've really enjoyed is, we can study it in the office, but then it really is a field activity. We have to be out there and look at our rivers,

measure our rivers. And so, one thing I've

really enjoyed over the years is that through work,

I've been able to visit all different spots around Alaska. And my plan is to keep

visiting different spots. I tend to spend anywhere from sort of one to three or four weeks

a year out in the field, either during breakup or during the rest of the

summer open-water season. So, breakup, really, what is it? It's in Alaska and we're up in the North. And what happens in the

winter is almost all of our rivers freeze with

a continuous ice cover. And so, that photo on the left is sort of the end of winter, sort of first signs of spring.

And it's what we see when we head out. And that's basically,

every river is frozen. The photo on the right is

sort of that transition. So, that's breakup where

we see some open water with some ice still in place. And that river is flowing sort of from the right through into the screen. So, sort at us. And that's really what breakup is, it's that transition

from fully ice covered to fully open water. This is the Yukon River, both on the left and the right, two different locations. And just to give you some perspective, the width of the Yukon River varies, but typical width would be

10 football fields wide. And so, in these photos, it's about 10 football fields wide or about half a mile or so. So, it's a big river, both in length and in width. So, when rivers break up, we always think about two

major types of breakup. On the left, you can see

we've got a thermal breakup and that's where the ice

sort of safely melt in place. We often think of these

as a good kind of breakup and a breakup when we don't get flooding.

And so, that's really what

we hope for each spring. The other type of breakup on the right is a mechanical breakup and that's where the sort of force of the river flowing down river pushes against the ice in place and mechanically breaks it

up and can form ice jams. And we'll look a little

bit later at an ice jam and actually see a jam

that forms and releases. Generally, years with

a mechanical breakup, we tend to see ice jams. And those are the years where we can see ice jam flooding throughout the state. The photo in the center is Akiak.

This was flooding caused

by an ice jam in 2009. And in 2009, it was a dynamic

breakup across the state. And we had ice jam

flooding on the Yukon River and other major rivers across the state. Akiak is on the Kuskokwim River, which is just south of the Yukon River. So, just a quick look at an example of a thermal breakup. I think the picture on the right really shows what happens, how the ice just melts in place. And this would be similar if you live near any lakes or ponds, those are always thermal breakups. The ice just melts in place, changes color that affects

how quickly it melts and just loses strength. One interesting thing

to note in that picture and this is typical with breakup throughout the state is, is it's always generally snow free. The snow melts in these

old lower elevation shelf well before the river ice breaks up. This is Napaskiak again

on the Kuskokwim River. If we look on the left,

that's a similar image. It's the beginning phases

of a thermal breakup.

We can see the ice is starting to darken. We can see outside of the river and it's already free of snow. And the other really

interesting thing to note, which is really important in Alaska is that we've got the… You can see that line that goes through the center of the river and that's an ice road. And so, one thing, ice is really important to Alaskans for travel in the winter time. Normally, all those

communities I showed on a map, you have to fly to.

And that's how I've

gotten to all of those, is by air. But in the winter time,

they'll build ice roads. Communities will build ice

roads from one to the other and it's much cheaper to move groceries, packages on an ice road

than to fly them by plane. So, during breakup, communities are really concerned about, "We can travel on the ice, then there's a period during

breakup when we can't. And then once it's open

water, we can travel by boat." And so, often communities are interested both in ice jam flooding and also how to get back and forth. So, what the status of the river is. One of the common terms you'll hear for thermal breakup is mushout. It's a really mellow, mushout, no flooding expected. If we look at mechanical breakups, this is where we get ice jams form and we can have flooding. On the left is Eagle, Alaska in 2013. So, that was another year where we had mechanical

breakups throughout the Yukon River and the Kuskokwim River. And what happens is that ice jams forms and then upstream of the ice jam, the water level rises.

And it can rise enough

where it actually pushes chunks of ice outside the river. And so, you can have both flooding and damage to homes, trees, structures from the ice itself. And so, you can look at the picture of the ice on that road. It doesn't look that thick, until you stick my boss

against that ice chunk. And he's six foot six. So, that's sort of gives you

an idea of how destructive or how large these chunks ice that can flow over the riverbanks can be. This again was Eagle in 2013. If we took Eagle and sliced the line through the center of the river, this is what an ice jam

looks like in cross-section. And so, on the right

side of the photo image is ice in place. And that's sort of our sheet ice that's been in place all winter. And then we've got the river flow coming from left to right. And that's providing the force against the ice that can break up.

And if it gets stuck, chunks of ice keep packing in to this ice jam front, we call it and create an ice jam. And then upstream, you see on the left side of the image, we get increased water levels and they can go up enough to flow over bank into communities. And you can see what we saw on Eagle is that it enrolls enough so that some of the chunks in the

ice jam actually blow it over bank onto the roads, pushed homes off foundations.

Often, we're interested

on where jams occur. They occur at river construction such as bridges in the lower 48. Many of the ice jams occur

at bridges in Alaska. If we look at the Yukon River and the Kuskokwim River, we have one bridge that crosses those two. So, we're not as concerned about bridges on our big rivers. Sharp meanders, obstructions, islands, changes in river slope. That would be where the river comes out of the mountains and then hits a flatter area. The picture on the left is one of the most famous

ice jam locations in Alaska. And so, we call this Bishop's Rock. You can see the waters

flowing sort of towards us past this rock on the left

side of the river there and ice jams can form. And then 20 miles upstream

is the town of Galena. And so, in 2013 and another years, ice jams that formed

at Bishop Rock flooded the community that was 20 miles upstream. Here's a quick look at Galena. So, this is looking downstream from Galena and Bishop's Rock would be 20 miles in the distance there. The map on the right gives you an idea of where Galena is.

It's about two thirds of the way down on the Yukon River towards the mouth. And this is an image of May, 2013, when an ice jam formed at Bishop's Rock and flooded a majority of Galena. It's interesting to note that often the right side of the image, you see a dry area and

that's protected by a levee. And so, there was a portion of Galena that was protected by a levee. Another portions that did stay high and dry weren't effected by floodwaters. (indistinct) to do next, we saw that cross-section. What we'll do is we'll

take a look at an ice jam. So, the next screen, I'll pull up a time-lapse video from Dawson City in

Canada, Yukon territory. And it's basically the day in the life of the Yukon River at Dawson City when it breaks up back in 2011.

So, I will switch. And Lisa, can you confirm that I switched? – [Lisa] Yep, I can see the video and don't forget to unmute yourself. – [Crane] Thank you. So, this video is one day in Dawson City. We've got in place sheet ice. The river here is flowing right to left. So, from our right to our left and what we'll see is a sort of typical spring day in the North. I think some snow comes through, sun keeps spinning around and what you'll need to watch

for is some rapid change and then look off to the

left side of the river and you'll see an ice jam form. Snow's not uncommon in May. This is May 7th, 2011. And here's the river breaks out. And then the ice jam forms

on the left side there and then that ice jam releases. And then what we'll see

is there's a ice flow, we call that and that's the ice jam that really stopped

streaming flowing through and then another ice flow

starts two additional ice jams that formed and released.

And so, in this case, it was a mechanical breakup. It happens that quick. I've been there on rivers that break up. And usually everybody has a feeling that it'll happen soon. And so, the community's out watching. Within a matter of minutes, the entire river starts to move. So, I think what we'll do is we'll pause for any questions on a

breakup and ice jams.

– [Lisa] We had a couple of people who had a little bit of a problem with the audio when you were talking when the video was on. So, maybe you could

share your screen again and then that might help with

folks hearing your audio. And for folks who can't see the video, it might have been that the video screen opened up behind your window. So, that might be another solution. But one of the questions

that we did have was, Theodore was wondering,

"What was the worst flood that ever happened from ice jams?" – In Alaska, I think

one of the worst floods was 2013 in Galena.

At least in recent memory in sort of my professional career, probably in the last 30 or 40 years, that was one of the worst

ice jam floods in Alaska. – [Lisa] And an associated

question to that is, how long do the floods last usually from an ice jam? – That's a good question. And just a follow-up

on the first question. The damages at Galena

were about $70 million for that 2013. So, as far as how long they last, that is unique for ice jams, they can last days. A typical sort of river

flood from rainfall would be on the order

of one or two days rise and then fall.

Ice jams are unique. And that Galena held for several days for the water just

continued to rise slowly and then release. We had an ice jam on the

Kuskokwim River last year that stayed in place for nearly five days then released. – [Lisa] So, Theodore was also wondering, "What can people do about

mechanical breakups?" And you might perhaps

going to talk about that a little bit later on, but are there things that people in the villages can do? – I will cover that. And I'll say the best thing

people can do is prepare. There's not much we can

do to prevent ice jams, but preparation right

now, this time of year, a few weeks before breakup is the time people can prepare.

– [Lisa] So, Anna Maria was asking, "Why do they give names for the ice jams different parts?" So, you showed that diagram of the ice jam and she was wondering, why do they give the different… Are there different

structures within the ice jams that have separate names? – There are and I could show

a much more technical figure that identifies each part of the ice jam. And I think it's primarily so hydrologists can communicate to other hydrologists where the tow of the jam is. That would be where it's actually meeting the in place ice. Where the top of the jam is. Sort of the jam itself, we'll often call the equilibrium section, which just means it's sort

of in place not changing, but it would be like sort of your bike has every little part labeled so you can talk to the mechanic and it's just more for communication.

So, I think it's similar to that. Any science will have

sort of technical terms for all the different parts. – [Lisa] And we had another

question about floods and you had mentioned that 2013 was a bad flood year for Galena. Was it a bad flood year

on all of the rivers or is it specific to different rivers? – Typically, when we

get a mechanical breakup on the Yukon and the Kuskokwim, it can be bad flooding

in more than one spot. The sort of mechanism just repeats itself.

Rivers break up from

upstream to downstream. And that year in 2009, there was… 2009 and 2013, there

was flooding at Eagle, which is upstream from Galena and then at other communities down the way and then finally at Galena. And so, it's not uncommon to

have sort of major flooding at 5 to 10 communities in the same year. Years we have thermal breakups, there's typically no flooding, but years when we have

mechanical breakups, it's typical to have one or more than one locations have flooding. – [Lisa] We actually had

another question about ice jams. So, are each of those flooding events caused by separate ice jam or are they all (indistinct). Can you have several flooding events that are caused by one ice jam? – That's a great question. Generally, an ice jam forms and floods the upstream community, just like it did it Galena. When that ice jam releases, it can also flood downstream communities because you've taken sort

of a big bath tub of water and pulled the plug when the jam releases.

And so, that same jam

can flood downstream, not necessarily from an ice jam, but just from sort of

release of a tub of water. But generally what happens is an ice jam will form in Galena or let's say Eagle, really far upstream flood Eagle and then it'll continue

to mechanically breakup. That jam will release just

like we saw in Dawson City. And then another jam will form, say downstream from Circle or from Yukon, one of the other communities. And so, generally, it's different ice jams that flood the different communities. On our rivers, on the Yukon, it's probably between 50 and 100 miles between communities, whereas on the Kuskokwim, maybe 5 to 10. So, they're much closer down there. – [Lisa] Gotcha. Texas was wondering, "What conditions cause mechanical breakup versus a thermal breakup?" – That's a great question.

And I'll cover it a little bit at the end, but it's generally the

sort of competing forces. Snow melt providing

more water to the rivers and then the ice in place losing strength. And so, when there's

smaller amount of snow melt and the ice loses strength,

it's a thermal breakup. And years when we've got sort of cold, strong, hard ice and

a rapid snow mountain, that's when we get mechanical breakups. – [Lisa] So, Anne had

asked a related question of what weather events

proceed a bad ice jam. So, you're talking about the key elements being snowpack and ice. The ice thickness and stuff. – Yeah and weather plays a big part. So, we've identified sort of two unfavorable weather conditions. That would be record warm temperatures towards the latter part April and that can lead to ice jams.

And the other unfavorable weather pattern would be cooler than normal conditions through the entire month

of April and early May. And so, that delays snow melt and then keeps our ice strong in place. And then we get rapid snow melt in May. In 2009 and 2013, our interesting one had

record warm temperatures that caused ice jam flooding and the other had a prolonged cool spring that delayed breakup. – [Lisa] That's really interesting. Well, I think we'll hold on to the rest of our questions for now. And then we'll go onto your next section 'cause I know you have

a lot to share with us. – That sounds great, thanks. So now, I'll jump into the program that we called River Watch. We, as the River Forecast Center, monitor rivers throughout the winter. Towards the end, I'll provide our outlook for 2021. But really what we

understand as hydrologists is we can't predict when

an ice jam will occur and how severe it'll be. We can lean towards they're

more likely this year or less likely this year, but really to provide information for communities we need to be out there. And so, the plane on the left, that's what we do.

It's a joint mission

between the State of Alaska, local communities,

elders that we work with and the Weather Service to monitor breakup and we do it from the air. The map on the right is

sort of the map of Alaska. The rivers aren't white. And then all the communities of concern or the communities that

could have ice jam flooding, are the little dots along the rivers. And so, throughout the season, we'll change this map and

show the community status whether there's a warning, a watch or an advisory in place. And then the river status

shown to the right, we'll change that as the rivers go from completely ice covered. At the end of breakup, everything is blue or open. The center image or

some of the newer tools, typically, River Watch has

been this aerial mission where we fly in small

planes throughout the state. It lasts for about three to four weeks.

Starting about the end of next week, I'll be up on the Yukon

River for about seven days. I'll fly from the border all the way about midway down river. But we've started to use

more and more newer tools that are sort of space born

tools to monitor river ice. And so, the center image is sort of like a Google earth type image that's from a satellite in space. And what we do is we

try to classify the ice or the river as ice covered or open water. And so, we're using more tools like this, but we're still not at the point where we can sort of transition from our typical monitoring from the air. And this is just another

picture of this sort of transition from frozen

rivers to open rivers.

This is what I'll be monitoring for 7 or 10 days next week. Basically, we try to

watch the breakup front. Rivers break up from

upstream to downstream. So, in the Yukon, it's sort of river

flows from west to east. And so, we'll start all

the way on the west side, monitor breakup as it moves down river and be trying to track this

break up front, we call it. And so, the river is flowing away from us. And if we look at the distance, we can see it's completely

ice covered in place ice. Just solid in place ice. And then it transitions

to what we call sheet ice. We've got some larger sheets and then we have a technical current term, just chunk ice for the

small little chunks. And that's sort of the best kind of ice to see during breakup. It's been ground down to

small chunks that won't jam. And then if we continued up river here, we'd see it's completely open. And so, what we'll do is we'll track this for almost 1200 miles, this transition and be monitoring for ice jams.

I think we had a great question before about what we can do. And really we can't stop

or prevent an ice jam, but what we can do is provide warning and provide time to prepare so we can identify when ice jams forms. And then let the community know quickly that an ice jam's formed and they have to prepare

for imminent flooding or flooding that occur within hours. This is a picture again, a little closer up of Galena and you can just see how

jumbled the ice jam is, but the toll of the ice jam or the furthest downstream

portion of the ice jam was that Bishop's Rock. Another look, Galena is (indistinct) the distance there. This is the same time period. This was 2013 and just a quick look from Bishop's Rock all the way upstream. And so, you can see this is (indistinct), where do ice jams form? And it's areas where the

river changes course quickly and also where we've got obstructions.

So, we've got two things. We've got this ice bend and then we've got the obstruct that pinches in on the Yukon River. And so, this is just

a view of that ice jam as it occurred probably same day as the previous picture. So, it doesn't look like much here, but then as you as you move upstream, you'll see more jumbled and jammed ice towards Galena. So, what we'll do is I've got a video from a River Watch mission back in 2015 that we'll look at it. I think gives you an idea of exactly what we do in the air and how we communicate directly to the communities on grounds.

So, Lisa had mentioned you may need to bring the view maybe

behind your browser. And once it loads here, I'll hit play. Okay, it's loaded and I'll hit play. – People are in the

village, they can't go out. And they don't know what the ice is doing. So, with information like that, it prepares the people and they have knowledge about what's happening in their area. And that can go long ways. (indistinct) – Good evening, (indistinct), this is River Watch. (speaks in foreign language) There's been a report on the up river ice. (speaks in foreign language) About a mile and half and it appears to be ice-free from there. – [Woman] All emergencies are local. And so, in working with the communities and in working with the scientists over at the Weather Service, we're able to join together

some important partners in dealing with emergencies

and preparing for them and just doing our best

to keep each other safe.

– [Man] The significant

ice is between Aniak, and Kalskag and (indistinct). – [Woman] Can you characterize this as a (indistinct) or more of just place where it's rotting in place? – [Man] I call it sheet ice in place. – [Man] The Kuskokwim

and the Yukon are unique when we are actually flying, but there's also the Coy Cook, Buckland, the Noatak. And so, those are more… We're calling communities, finding out what's going on, trying to give information back, provide information that

we've heard back to those, but the Kuskokwim and

the Yukon are the two that are unique where we fly each year. – [Woman] River Watch is a great reason to reach out to the communities.

Everyone's interested, everyone's already ready to talk to us. So, we just give them a call, touch base as often as we can with pretty much anyone who's willing to answer the phone for us, make sure that we have information and can contact all of the communities if there is something

happening anytime of the year. – A lot of calls that I got, we're wondering if there's

during (indistinct), if there's more ice upstream. Yes, there's 60 miles of ice that's above Bethel

still yet to come down. I do enjoy reading river ice and watching breakup. It's to me, a very

important time of the year for a river. Our river is our lifeline.

– [Crane] I'll go ahead

and share my screen. – [Lisa] So, we did get

a couple of questions from the video and what you were talking about with River Watch if you have time for a few questions here. – Go ahead and do that, that's great. – [Lisa] Okay! So, Carol was wondering, "How many people are assigned

to fly the Yukon River when you're doing this. We noticed that there were

several people in the plane." – So Carol, that's good question. Typically, what we do is, it's a partnership with the state. And so, there'll be one Weather Service on-state employee. And then Peter Atchak was

a local community elder that flies with us occasionally. So, probably two to three, sort of the core River Watch mission. And we break it up into

sections of rivers. In the Yukon, there'll be three teams.

I'll do the upper Yukon. We've got a separate team

on the middle and the lower. And so, overall on the Yukon, we have anywhere from 6 to 10 people involved in River Watch, but just one team's out at a time. I'll be out for about 7 to 10 days. Middle Yukon a few days and then lower Yukon about a week. – [Lisa] And a related

question to that is that because you were talking about how river breakups starts at

the up river end of things, because you only have one team out on the river at a time, does the up river team

go for a certain amount of time until breakup

happens on that upper part and then you switch to the middle or are you flying the whole

river at the same time? – Usually, it will transition. It's a progression from

upstream to downstream. Usually, it's not

time-based, it's location. So, when break up is

downstream of Steven's village and upstream of Tana village, we transition to the middle Yukon team.

So, it's TBD. TBD determined how long I'll be out there. And then the same with

the middle and the lower. The Kuskokwim is a smaller team. They fly the entire river. That River usually breaks up on the order of 7 to 10 days total. So, it's just one team

of two to four people that fly the Kuskokwim. – [Lisa] Eve was wondering, "Do you also collaborate

with teams in Canada because we know that the

Yukon starts out in Canada and moves through Alaska." – We do. And that's one of the main parts of working in the RFC. Most government agencies are tied to the border, the US border. And as you saw, the Yukon

River goes into Canada and about a third of the Yukon watershed is on the Canadian side.

And so, we do collaborate

with the Yukon territory. And so, we sort of trade river notes throughout the season and then share our outlooks with them. And then as they begin to break up, they have a similar River Watch mission. And so, there has been

times over the years where the US and the

Canadian River Watch teams will fly past each other when breakup is right near the border. – [Woman] Wow, that's pretty cool. So, Theodore was wondering, "What kind of plane do

you fly on the surveys?" – It's usually a small Cessna, a 207. Occasionally, a small twin engine, but it's usually on the order of five to seven passengers small plane. – [Lisa] And he also wanted to know whether you fly one. – I don't, one of the few. Always wanted to, but I think work and other things have gotten in the way. – [Lisa] And let's see. So, Carol was wondering about… On the video, we were

seeing that the folks in the plane were giving reports out by radio, I believe. So, who are you talking to in the villages who you're giving supports to? – Yeah, that's a great question.

It's unique in Alaska where communities use Marine radio for communication. And that was before we had telephone or even cellular phones. It's just in the last 10 years where all those communities

in Alaska started to get cell phones. And so, prior to that, it was cheaper and easier

just to use a Marine radio to communicate within the town. And so, what we do is we talk direct from the planes to the communities on whatever local frequency to use. And we just basically

broadcast on what we've seen. When we get a local community member to fly with us like Peter Atchak, it's great because we can

give a brief in English and then Peter can translate

into the local language. And so, that's helpful. So, it is sort of direct

to the community members. – [Lisa] Do you have community members from a lot of different communities who fly with you? – From year to year, it varies.

Typically, in the last two years, it's been challenging under COVID. And so, this year, we still aren't sure how we'll handle partnering

with local community members, but typically, if there's a tribal member or local city official that's interested, we'll try to… Especially, if there's a concern locally, we'll try to include

them on a local flight at least to let them know and see what's happening

upstream or downstream.

But typically, probably we get three or four community members

that participate each spring. And we really draw… I think I can completely relate to Peter watching river ice, it's just fascinating. And he's got five or six

decades of experience that we can learn from. – [Lisa] And related to

that, we were wondering, are there traditional knowledge histories of different flooding

events that have happened and where they've happened? – Definitely, yeah. And we lean on our local

partners for names. Most of the names we

use aren't on USDS maps. They're often somebody's fish camp or a traditional name for abandoned river and often they're associated

with ice jam locations. And so, we try to sort of gather as much as we can during break up as we work with local partners and then document it on our maps so that in the future, we're prepared to sort

of use the same names that they use along these rivers.

– [Lisa] Wow, that's

a great example of how the traditional knowledge

from the local areas can augment your maps and sort of document all of these events. – Yeah, I always joke with folks and I'm serious, when we call out, usually, one of our strongest, one of our tools we'll

use is the telephone and we'll call out to a community and often we'll ask, "What do you think? Are you concerned? Is this something you've seen before?" Because from the office in Anchorage, from satellites, we can't measure that or detect that, it's the local community

that sees it year to year. And we help communicate

that up and down river. So, partner with those members. – [Lisa] That's great. I've often thought about how we have these highly technological ways of gathering information, but we always need to

have that ground truthing of what's going on at the ground level that people can see.

– Definitely. – [Lisa] All right, well, let's hold on to our questions for now and we'll go on to your next section 'cause I know you have some more things to share with us. – Sounds great, thanks, Lisa. And you can see my screen, I'll advance to the next slide, which we just covered. I'll just highlight the photo. This is Aniak on the Kuskokwim river. And so, an excellent area of concern. And this is breakup a few years back and just sort of shows. And this is mechanical breakup, but there was no ice

jam flooding this year. So, what I talked about, we can't prevent ice jams, but what the Weather Service

can do is provide warning. And so, what we do is we've

got two main products, sort of that one in the middle. How we do it is go flood watch. And so, that's where we tell communities things are favorable, time to watch, time to get ready.

And what we do is we'll issue that from the plane

direct to the communities. And we'll say, "We are

worried about an ice jam. And so, we're going to

issue a flood watch." And the first message will just be verbal. And then we'll go back to the office, we'll relay back to the office, they'll issue a flood watch that would come over the

TV or over the radio, but really from that plane, is the direct communication and then the next level

up is flood warning. And so, that's the take action. It's happening and water's going to rise. It's imminent now as this is the time that all your preparation is done and now you need to probably relocate. They'll say and sort

of local evacuation go to high ground, move

anything up that you can, but the ice jam's formed and expect the water to rise.

And so, those are the tools that we have through the Weather

Service to let people know. But I think the real sort of amazing part of River Watch is that it's usually direct from the plane to the communities. And so, I look at it as just a great… It's the federal government, the state government and then locals, all on the same page for breakup. So now, we'll look at sort of where we think we're at for 2021 or this year's breakup. And so, there's three main

components we consider when we look at the breakup outlook. And so, the first one is ice. And so, we're interested in

the thickness of the ice. And if there were any unusual

conditions in the winter that would lead to

jumble at ice formations or areas of our rivers that

are thicker than normal, the next ingredient is snowpack.

And so, that's upstream in a watershed and that's the amount of water that would be available to melt and then flow into the rivers. And so, more snow tends to heighten our awareness

towards a mechanical breakup. The other sort of competing

factor personnel pack is that it functions as a blanket. So, if we had a heavy

snow pack on the river, sometimes that can actually

slow the growth of ice. And then the third

component is spring weather that I touched on earlier. And so, that spring weather is probably the most important factor determining whether it'll be a thermal breakup or mechanical breakup. We tend to have outlooks

based on the first two. And then what we really need to do is sort of watch the weather as we get through April and May and highlight if we're headed more towards thermal or mechanical.

It's really those late April and May temperatures that control. And I sort of highlighted the two unfavorable conditions, that would be record warm temperatures. 2009 was a great example. I was in Fairbanks doing snow surveys, sort of field hydrology. And I remember, 70

degree days right around the end of April, which was

record highs at the time. And then that year we did have ice jams. And then the other sort of unfavorable is if we get just cool conditions throughout the month

of April and early May. So, this year I'll look at the three components briefly. The first is ice thickness. And so, on the left, what we try to do is

measure the amount of cold that happened all winter. And so, we have a term we

call freezing degree days. And so, each day we figure

out how far below freezing the average temperature was. And then we add that up

to the entire winter. And so, it's sort of a measure

of how cold winter was.

And then we compare

that to previous years. And so, on this map on the left, you can see if it's

wide, it's near normal, if it's shades of blue, it was a little colder than normal. And then shades of yellow,

a little below normal, but in general, everything within Alaska was near normal sort

of 90% up to 110, 115%, but sort of in that normal range for the amount of cold

throughout the winter. And that we try to

relate to ice thickness. So, just from the air temperature, we'd expect probably

near normalized thickness throughout the state. It wasn't very thin and

maybe it wasn't very thick (indistinct) conditions were forming. So, then on the right,

we need to ground truth because we've got sort of snow and ice and the way they relate together, can drive how thick the ice is. And so, we work with local observers throughout the state and try to get actual ice measurements. And so, the map on the right shows the actual ice measurements at the beginning of April. And you can see the shades of green are sort of in the normal range, then I'll get to areas highlighted.

And so, on the right is an area where we see 127% of normal. So, that's thicker than

normal ice this year. And it circled that

area because reports… We keep track of rivers

throughout the winter and the reports from locals and multiple locations

on the Yukon river there were we had freeze up jams and we have thick jumbled ice between Eagle and Dawson City to the point where they couldn't put any snow machine trails on the river. It was too rough. So, that's definitely an

area we're concerned about. We've got thicker,

stronger ice than typical. And so, we'll watch that area closely. And then the other area of highlighted, sort of on the left with

the blue square is Galena. And so, we've got a nice

thickness that's below normal. And since we got this

measurement back on April, 1st, we followed up with several

communities near Galena and it is that ice

thickness is representative of conditions around Galena. Due to the thick snowpack, it sort of formed a blanket and didn't allow that cold air to freeze the ice very thick this year in the lower Galena, in

the lower Yukon area.

The next sort of ingredient

I talked about was snowpack. And so, the map in the center is a map of Alaska snowpack on April, 1st. And the way we look at that is this is shades of blue in the Cape. Deeper snow, more snow than average. And then shades of red are thinner snow or less snow than average. And then the real sort of key message here is the dark blue in the

bottom left of the image is the Kuskokwim River Basin.

So, one of those big

rivers we've talked about, we're concerned about and that has 180% average snowpack. So, it's much thicker

or much above average for the snowpack in the Kuskokwim. So, there's that much snow that can melt and sort of drive the river ice during the breakup time period. We're also concerned, like I mentioned, we've got to go into Canada.

And so, on the right

is the same map put out by the Yukon territory. And shades of blue, again are above average snowpack. And so, if you look at

the Yukon River upstream from the US border, we've got about 125, 130% of average. So, it's slightly above

average there as well. So, if we sort of combine

our look of river ice throughout the state,

our understanding of it and then our understanding of the snowpack throughout the state, we come out with our breakup

outlook based on those two and that sort of general

understanding of the weather for the next three to four weeks. And that's probably the hardest thing to really predict is the weather. The Weather Service is really good for the first seven days. And then beyond that, we look at sort of general outlooks. Will it be above normal or

below normal temperatures? We don't have any tools that could predict or record high temperature

day in three to four weeks.

And we don't have any

tools that'll tell us if we're going to have a six-week long, prolonged below average temperatures. We have tools that can tell us one above or below is more likely, but we are there with the tools that could really tell us if we've got these

unfavorable conditions ahead. But if we look at those, those two are three factors. We think that we're

trending towards mechanical on Alaska's major rivers.

At the bottom there, we're shifting our outlook

towards mechanical. Some years, we're way over to the right. Over the last seven or eight years, we've been mostly over

to the right and thermal. And 2020 and 2021, we're sort of towards

the left and mechanical. And then throughout the state, the two areas we're concerned about are the Kuskokwim River with

that above average snowpack and then the upper Yukon

River, Eagle and Circle with above average snowpack

in the Yukon territory. And then that mid-winter

jumbled ice that's in place. And then throughout the rest of the state, we vary from sort of

average flood potential to below average in some locations. We put out our outlook

in graphical format. And so, this is a map of Alaska. It's got our river shown. The major river East to West is the Yukon. And so, each community

that we're concerned about for ice jam or ice

flooding, has a little dot and then we sort of

rank the flood potential based on where we are this year and related to the

historical amount of floods they've had in that community.

And so, Yukon, you can see two yellow dots up near the border and that's Eagle and Circle, sort of in the moderate range. And then the Kuskokwim, is that river down to the lower left with quite a few yellow

dots in the moderate range, primarily due to that snowpack. And then other rivers

are generally colored sort of in the low to low

to moderate flood potential. And that's related to how likely it is to flood on any given year. Some communities that are low or just they're very elevated and not susceptible ice jam flooding. But it's always… I think what I've learned

through monitoring breakup is that even on a low-risk year, there's still a risk and the communities are always

concerned about breakup. It's the time of year

when flooding could happen on any given year. And it's the time to really

prepare and be alert. The other thing we look

at is breakup timing. And that's related to

people want to sort of plan or understand, "Are we going to have to wait a little longer

to get our boats out? Are we going to be able to

get our boats out sooner?" And so, this is just a general lookup, breakup timing throughout the state.

The one community I underlined is Nikolai on the 23rd of April. As of today, it hasn't broken up yet. And so, we'll look at that as an indicator of if we're early or late and that's the first spot that we monitor. And so, in general, we

think breakup might be on the order of one to a few days late throughout the state.

So, maybe we'll stop there and take questions on the outline. – [Lisa] Yeah, so, Theodore was wondering, "Is there a breakup happening

right now somewhere? You had mentioned that next week, you're going out on the Yukon. And so, we were wondering whether you had already gone out and whether there's potential or there is some breakup happening." – So, it's interesting

because this morning as I started just to check email, we had one river gauge South of Anchorage on the Kenai Peninsula

that had unusual reading and we suspect that it broke up and there's an ice jam. We followed up with the fire department and it sounds like there's

an ice jam in place. It's not one we monitor by air and the impacts are minor. It wouldn't flood a community. There are some roads, campground a few homes that could be threatened, but we are just at the very front edge of breakup in Alaska. And so, the Anchor River is the one that has the ice jam.

It broke up today. And that's two days late on average. So, it's sort of tracking

with where we think that breakup will be delayed after the average date of breakup. – So yeah, everything is

starting to happen right now. I have one more question

before we go to… Actually, two more questions before you go to the next section. We have about seven minutes left. So, I want to be conscious of our time. Texas was wondering whether

you ever use man-made or mechanical ways to break up an ice jam. – So, we, as part of

the River Watch program and as part of how things are handled in Alaska, we don't. The sort of the state

and the Weather Service doesn't use any mechanical methods.

Usually, if it's a mechanical method, it'll be the local town, local city. And so, as an example, last year, there was an ice jam

that formed mid-winter in Willow, Alaska and the borough used mechanical excavators to remove that ice jam. And so, it is done. It's not something we're typically part of as sort of the River Watch mission, but the small scale cities, communities do sometimes take action

to remove the ice jam. And in that case, they use the excavator to actually just dig out the river and remove the river ice. – [Lisa] I'd imagine with those ice chunks being as large as they are, you'd need a pretty large

excavator to do that.

– It was a much smaller river, Willow, it's maybe 100 feet across. 1 to 200 feet across. So, smaller ice chunks. Historically… – [Lisa] Huh, go ahead. – Historically, there has

been the use of explosives, but typically, it's not

found to be very effective and it can cause more

harm than it does good. – [Lisa] Yeah, I'd imagine. So, let's see. Mabel and Ruby from

Arizona were wondering, "Do you ever enter guesses

in the Nenana Ice Classic?" So, I think that that's a good segue to our next section. And then you can answer that question while you're talking

about the ice classic. – Yeah, Mabel if you're from Alaska, we don't own the lottery, but we have the Nenana Ice Classic. So, I don't. I think our office is

like an unwritten rule that we probably don't

enter the Ice Classic. I don't know if we would

do any better than just… We have some tools, but

it is sort of process. We can't really pencil

out with an equation. And so, it's monitoring that's required. And so, we don't have a lottery in Alaska.

This is Nenana, the town of Nenana. It sits on the Tanana River. And every year for the last many decades, they stick a tripod out in

the middle of the river, which you see there in the center. And then they tie a string

back to a tripod tower. And then the string goes up

or pulley down to a clock. And when that tripod

moves 100 feet downstream, it triggers the clock. And whoever has the lucky guess for the hour and minute gets the jackpot. And this was from a few days ago. So, it's really something that everybody tracks in Alaska, is when it has the ice gone out in Nenana. And it's a great dataset

for scientific purposes because it's every year,

the same exact measurement. And so, we can track the breakup date over the last, almost 100 years. And we've seen that breakup happens about a week earlier at

Nenana on the Tan River than it has historically. – [Lisa] Wow, that's pretty cool. So, I know that you have

one more thing to talk about and we've got about four minutes, so I'll let you keep on going.

– I think we've got

one or two more slides. So, one thing really that

we're always concerned about in the spring time is ice safety. So, we're transitioning from ice cover we can travel on to ice cover that's unsafe. And so, really, it's a

time to talk to elders, talk to parents and evaluate conditions because there will be a time when it's unsafe to travel on ice. So, that's something we

always want to remind folks.

That picture is sort of the

classic truck through the ice and then trying to get it out. But it's a really dangerous condition that we want everybody to be aware of and we all know it. It's just a matter of understanding when that transition happens. – I think we're at the end there, Lisa. – [Lisa] Great. Well, we did have a couple more questions, so I'll take one or two questions before we have to go. So, let's see. Anna Maria was wondering, "Why don't you use drones?" – We do use drones and

often what we'll do, is some local student or community member will share drone footage

via Facebook or YouTube. And that's mostly how we use drones. We are in the air ourselves. And so, we don't really have that need when I'm out in River

Watch to have a drone, but it's great when a community member can sort of pop up and

take a look at the river and share that footage with us. – [Lisa] Great.

And then Nancy was wondering, "For communities that

are commonly flooded, have they had to think

about moving their villages or have villages had to

move because of flooding?" – They think about… Galena is a great example. Two floods, 2009 and then in 2013 was really significant. And what they do is they'll tend to relocate structures. Sometimes it's actually physically move the building to higher ground.

Sometimes it's relocate and it's just elevate the structure. So, they'll elevate it

so that the first floor is above where we think ice

jam flooding could happen. – [Lisa] Great. Well, we're just about

at the end of our time. So, thank you so much, Crane for sharing all of this knowledge about ice jams with us. And I feel like we always

learn something new from each of our speakers and it's great to know how the knowledge is used to help out communities in Alaska. – That's great, thanks for having us and thanks for the great

questions, everybody. – [Lisa] All right, thank

you everybody for coming and listening to our webinar and we will be back next week to talk about North Pacific right whales. So, thanks very much.

Bye-bye..